We’re living through an abrupt, even violent, shift towards the digital. Cooped up and distanced (I write this at the height of the Covid 19 pandemic) we instinctively reach for digital versions of our favourite things. Zoom meetings have replaced family get-togethers; Google Hangouts have replaced park benches, Neflix sessions have replaced… well, Netflix sessions – but you get the point.

But does digital always suffice? Are some things so profoundly tactile, sensory or Earth-bound that they get lost in translation when hosted in a virtual sphere?

I found myself asking those questions and more recently, when experiencing the Virtual Sandtray at the Play Well Exhibition at London’s Wellcome Collection.

Allow me to rewind a little.

Before there were virtual worlds, there was the freely available world of the imagination.

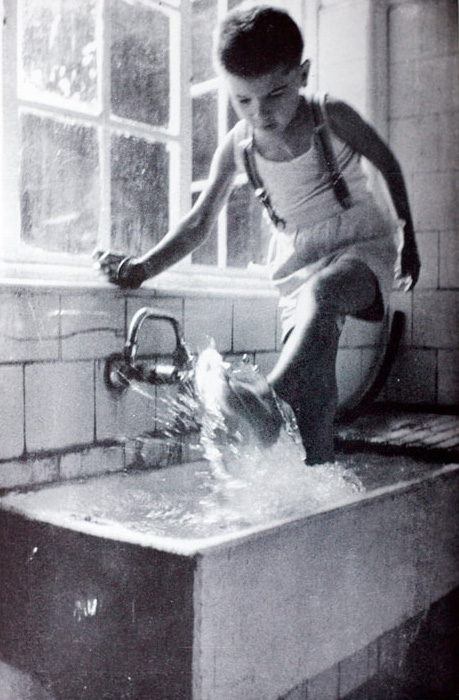

It was this infinite realm that child psychologist Margaret Lowenfield tapped into during the development of her ‘World Technique’ in 1929.

image © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library (via grasart.com)

The technique was developed at Dr Lowenfield’s (somewhat unenlightened-ly named) Clinic for the Study of Nervous and Difficult Children. It encouraged its young patients to create a spontaneous arrangement of toys and objects within a sand box tray. This would then act as a starting point for mutual exploration of themes by therapist and patient.

Almost a century later, I find myself sliding my fingers across a touchscreen (these were the innocent last few days before the viral outbreak) manipulating an assortment of objects and creatures across a blank digital landscape.

This is Virtual Sandtray – a computer-based solution for delivering a remote World Technique therapeutic environment.

Virtual Sandtray was developed by Jessica Stone, Ph.D. of Colorado, USA, in response to an emergency in child trauma care following the Japanese tsunami of 2011. She decided that it would be a practical way to distribute much-needed therapeutic material into areas where it would be impractical to start setting up physical sand boxes.

I think I might have been in a bit of a dark mood.

(image – M. Chrystie)

Initially she was frustrated by the daunting prospect of hiring in a development team to create the application – the lowest quote she received was $35,000 just to get to the concept stage. Finally, she turned to her husband Chris who, despite having no previous experience as a professional programmer, endeavoured to do the learning and software engineering to turn Dr Stone’s ideas into a working application.

I think it is particularly endearing in a world where media solutions are regularly constructed by large teams working across numerous agencies, that this enterprising couple pooled their resources, rolled up their sleeves, and crafted a solution in this manner.

However, when the outcome of the application of a digital environment is as serious as the therapeutic treatment of trauma in children, it is wise to debate – can a virtual world really act as a replacement for a long-established physical tool?

image © Thérèse Mei-Yau Woodcock, Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust and Wellcome Library (via grasart.com)

I admit I have some doubts. Using the app for the first time in position at the museum I am struck by how different the experience feels from a hands-on, physical rummage through a box of toys. Despite the enormous range of available objects (there are around 5,000 models available, some through expansion packs) I felt as though my creative process was being slightly railroaded; an inevitable consequence perhaps of having to navigate through a digital user interface.

And what of that tactile engagement that is at the heart of sinking your hands into a tray of sand (Lowenfield offered her patients both wet and dry sand as options)? What of the very physical nature of the activities of reaching, digging and placement?

To be fair, Dr Stone herself is very aware of this line of enquiry. She counters:

“I agree that the tactile is important… [but] there are so many other important factors of sandtray work, whether traditional or digital, other than the tactile.”

She goes on to highlight how the app opens up a wider world of creative options to the user (and it’s true – you would need a warehouse to store enough toys to emulate the apps inventory for starters); she also rightly points out the apps trump card – the amount of accessibility it delivers, not just to inaccessible locations, but also to people with disabilities and access needs.

Perhaps less convincingly, she also points out that some, though obviously not all, of the tactility of the activity is present in the form of touchscreen interactions (the app is tablet and VR only for this very reason).

(image – M. Chrystie)

I know that my own mind functions very differently in real-world environments compared to when my focus is limited to the contents of a screen, regardless of how engaging those contents are. I instinctively suspect there is something fundamental about the simple symbolism of toy objects, coupled with the endlessly shifting and transforming nature of sand, that opens up therapeutic avenues that an app of any kind is going to find difficult to locate and navigate.

The concept of a digital ‘sand box’ itself is one that has some existing cultural currency. Popular environments like Garry’s Mod, which allows you to freely model in 3D space using existing game assets, and Minecraft, and even The Sims, are often referred to as sand box games.

Obviously, I’m not in a qualified position to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of the Virtual Sandtray, whereas Dr Stone is. So, I’ll leave the last words on the matter to her:

“This App is not a replacement for traditional Sandtray work; rather it is an expansion which allows the amazing therapeutic gains of the traditional process to be used with more flexibility, in more settings with a more diverse population and potentially with less cost.”

Dr Margaret Lowenfeld Trust have a short video about World Technique – YouTube

Dr Jessica Stone has a (3rd edition) book about the use of games in therapy – Game Play