(image: HTC)

Let’s be honest – is it now even humanly possible to connect with the world’s most celebrated painting on any kind of satisfyingly meaningful level?

I have a checklist knowledge of its attributes – the ‘enigmatic’ smile, the poised restraint of the composition, but if I’m completely truthful I’ve hardly ever managed to feel very much from the object, simply because it feels so thoroughly obscured.

Obscured by the throngs of gallery visitors clamouring for their Insta moment; obscured by the overload of reproductions, reworkings and ironic rip-offs. This priceless image has flashed before our eyes so many times, it’s hard to recover any sense of its actual value.

In truth, I think that the Musée du Louvre, Paris are quite aware of this problem. As part of their Leonardo da Vinci 500 year anniversary exhibition they have commissioned Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass, a Virtual Reality work by Paris-based experience designers Emissive that attempts to bring audiences closer, in both emotion and understanding, to the iconic painting – to take them, as the title suggests, beyond the glass.

Emissive have a storied history in weaving engaging virtual worlds, and it seems that they take a great deal of satisfaction from their role. Co-founder Emmanuel Guerriero states:

Over the past 10 years, we have explored the interior of the pyramids in Egypt as well as the clockwork of high-end watches, taught rhythmic choreography to tennis lovers… and moved an iceberg across oceans. What was the common thread linking all these missions? Involving audiences in the most innovative and immersive way possible.

Taking on Da Vinci’s masterpiece posed a series of creative and technical challenges that were unique to the task. How to portray the sitter (presumed to be Florentine noblewoman Lisa del Giocondo). Do you attempt to faithfully preserve her famously enigmatic likeness, or dare to go further, revealing more about the woman behind the smile?

What about the (modern day Northern Italian) landscape that forms the background of the image? It is partially obscured by Mona Lisa herself in the painting; to go ‘beyond’ would take an imaginative vision of how it would be composed and populated.

In seeing how Emissive have tackled these challenges, I’m struck by the parallels between the artistic endeavours of creatives across the ages.

The modelling for the project utilised Autodesk 3DS Max, and some programming took place within Microsoft Visual Studio. Obviously, these are tools that were not available to Leonardo da Vinci (though, given his prodigious scientific output it wouldn’t surprise me if there were some scrawled prototype versions of them sketched out somewhere in the margins of one of his old notebooks!), but nonetheless, there are some interesting comparisons that emerge from witnessing the two processes.

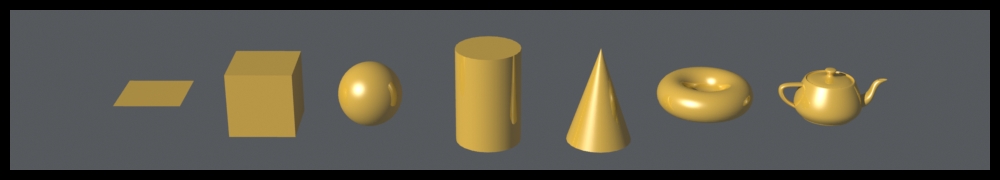

Emissive Interaction Designer Guillaume Martini, part of the team behind the project, said recently (talking at the design forum Homo Faber in Venice) that he likened 3D modellers to traditional sculptors because both started with ‘primitives’. These are the basic geometrical shapes that are the initial building blocks for complex 3D models. They are then extruded and transformed similarly to a sculptor working clay, or chipping stone from a block.

Martini goes on to say:

Digital [practitioners] rightfully deserve the title of ‘artisan’. There is a real savoir-fair in digital craftsmanship that has nothing to envy from its classical [counterpart].

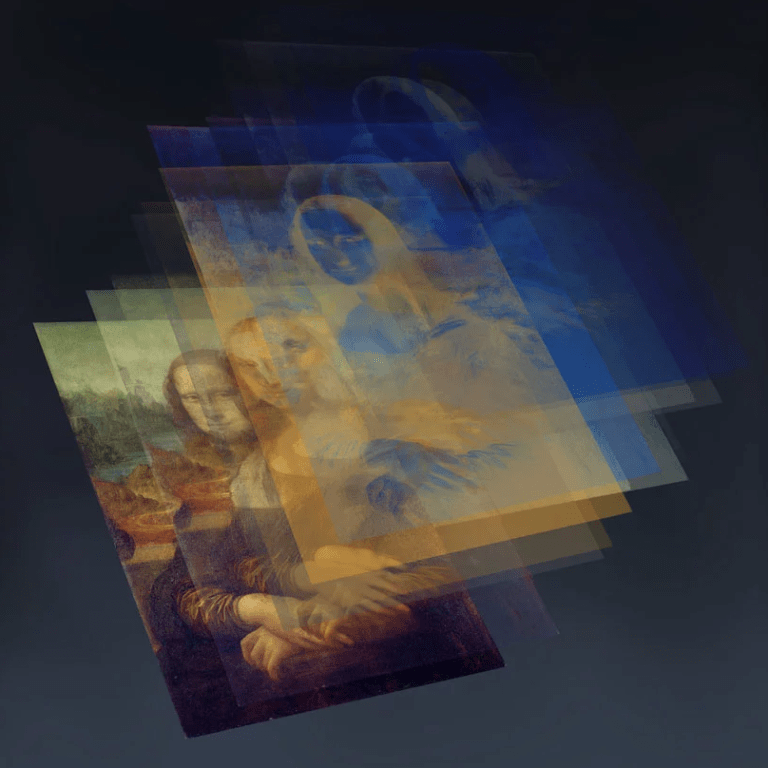

The VR resource highlights da Vinci’s use of the sfumato technique – he painstakingly layered on several translucent layers of paint to create subtle gradients of colour and tone. These layers used materials such as lead, vermillion, earth and varnish to create a raised glaze that gives the painting its vibrant ‘life’. Each layer was around 10-50 microns in depth (1 micron = 0.001 mm), and da Vinci is known to have painted on up to 30 thin film layers on occasion.

(image – HTC)

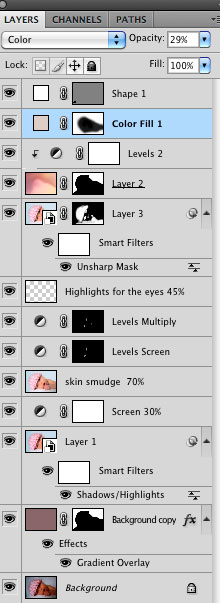

The process brings to mind the modern-day application of layers in imaging software such as Adobe Photoshop. It particularly reminds me of the use of blending modes, which similarly use the contents of superimposed layers to affect our perception of the image that lies beneath. These are mathematical functions with titles such as Multiply, Soft Light, and Overlay, that are commonly used during the composite process in the creation of digital imagery. While they apply quite simple algorithms to the relationship between image layers, the results mimic closely how natural light behaves, often resulting in satisfyingly photorealistic outcomes or dramatic creative effects.

(image: K. Hillerström)

While the techniques have similarities, it should be noted that todays digital image creators have it slightly easier when it comes to convenience. In contrast to the instantaneous effect of blending modes, each layer of paint applied using the sfumato technique would have had a drying time of days at a minimum – and in some cases months!

In the end Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass manages to strike an elegant balance between allowing the viewer an intimate and revealing audience with the work, and retaining an air of its inherent mystery.

In a fantastically detailed virtual rendition of the Louvre itself, we find ourselves before the famous mounted painting. The crowds of fellow visitors are represented by smoky wisps of colour, as though a timelapse sequence had somehow come to a halt. It’s an effective way of acknowledging the lingering obstacles to closely observing the work that exist in its real-life locale.

(captured by やのせん )

The louvre melts away and we find ourselves facing the painting’s subject as she sits poised and relaxed as the artist himself would have encountered her. There also are informative asides on technical and artistic elements of the work’s execution. Here VR really comes into its own, as it often does as an educational medium, as the viewer can glance across at the subject or study graphical representations of the innovative techniques used to render her.

(captured by やのせん )

Finally, we are swept away in a rather fanciful way by one of da Vinci’s other great works – his (hypothetical) plans for a wooden flying machine. This soars us high over the landscape partially depicted in the background of the painting. Again, this is a fine use of the medium as it gives us a chance to speculate as to how that landscape would have been imaginatively shaped by the artist himself, while also adding a unique perspective only possible through VR. It should be added that while virtual inventions can fly wherever we imagine them to, it is speculated that, despite his genius, Leonardo da Vinci’s invention would probably never have gotten off the ground!

All in all Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass is a very effective production, and one that brings the classical past to life in a decidedly modern manner. Crucially, I felt like it did help me to make something of a meaningful connection with the enigmatic and dignified woman who sat and modelled to such captivating effect all those hundreds of years ago.