(image – Harryarts / pch.vector / Freepik)

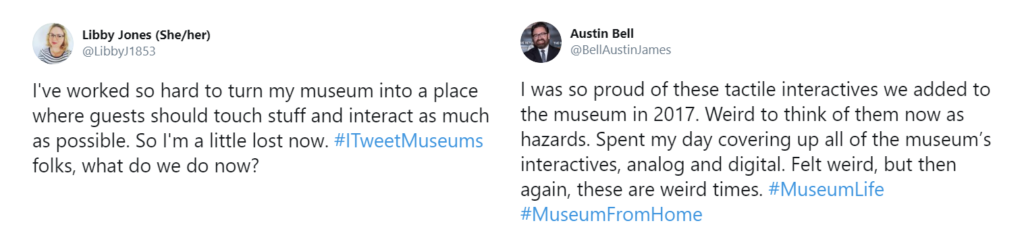

One of the many heart-breaking aspects of this Covid-19 pandemic crisis is that museums had only recently navigated a cultural shift towards encouraging visitors to get increasingly touchy-feely with the exhibits.

Tweets like these, from relatively early in the crisis typify the discord felt by many museum staff:

Our instinct, for the recent past, has been to break down barriers, remove the glass casing, and provide buttons to press and levers to pull. Visitor expectations have also swelled to meet the expanse of these newly endowed privileges.

It is going to be an uncomfortable bump to Earth if, upon reopening, museum touch screens and other tactile elements are taped over with a big ‘hands off’ sign.

This virus has already taught us a lot about museum’s place in the world. As much-loved institutions closed their doors (The Louvre, Paris, for example closed as early as April 2020) the hashtag #MuseumAtHome trended, as people found more and more imaginative ways to get their cultural fix under lockdown conditions.

The pivot to digital has been a defining factor in salvaging some continuity of provision of service for savvy museums. Those with an existing robust online presence have been grateful for it. Many of those with less of a prior digital cultural investment have been scrambling to catch up!

Of course, I am biased – as a filmmaker working in the sector it is in my interest to champion the virtues of digital media. But I think it is pretty clear that the plethora of moving image and interactive forms are going to be an increasingly important part of museum delivery going forward.

But with so much uncertainty around the nature of future public spaces – not just in the wake of this pandemic, but in preparation for any similar emergencies – how can museums design exhibits that can adapt and last?

I believe there are some existing concepts within experience development that can help provide ideas for better-equipped digital exhibits for this newly emerging landscape.

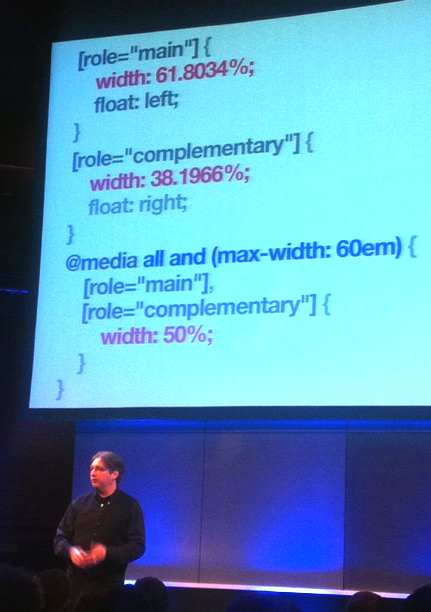

Responsive Design

One thing that has come sharply into focus during this crisis, is that we live in an unpredictable world. Exhibits will need to be a lot less rigidly designed in future, with a built-in degree of adaptability.

As a potential template for this, we might want to reference the changes that web design has had to make over the years.

Because of the proliferation of mobile devices, each with their own screen size, resolution, and even differing input methods, website designers have had to come up with ways of ensuring they can provide a flexible resource that can adapt to the confines of whatever combination of devices their target audience chooses to access them on.

These days, it is perfectly routine for web sites (like this one!) to automatically and elegantly respond to whatever device they find themselves serving – a process labelled Responsive Design.

(image – iconicbestiary / Freepik)

Likewise, I imagine that exhibit designers will increasingly have to plan for potential state changes to delivery that are imposed by external factors, such as a requirement for social distancing, or a sudden reduction or increase in visitor numbers.

It may well be, for example, that a project designed to produce material for an interactive exhibit also ensures that its outputs can be readily reworked into an online version if need be. This kind of thinking will equip exhibits with the valuable ability to pivot at will.

Graceful Degradation

Here’s another concept carried over from web design. The internet has always been designed to be fairly bomb-proof! The idea behind graceful degradation is that if parts of your system don’t work properly, the remaining underlying parts still look good enough to the end user that your production remains usable.

(image – Faruk Ateş)

This manifests to good effect in web-based text and object formatting. If your browser can’t read all of the formatting for a particular line of text, it applies as much of the underlying formatting as it can, using a hierarchy of inheritance to work out which elements to give priority to.

I imagine a similar line of forethought might be useful for future-proofing digital exhibits in general terms.

Start by attacking your exhibit from all angles – how would it work if you were no longer able to use any of the input devices? What if you had to suddenly reduce the screen size by two thirds? What if there was a requirement to remove all of the sound?

How would the other systems within the exhibit cope? Are there ways in which you could inherently mitigate for system losses by compensating with other things?

An example of this might be an exhibit that, while designed wholeheartedly as a visitor interactive device, also works perfectly well as display-only exhibit if circumstances require it.

Platform Agnostic

Exhibits with a built-in ability to pivot are going to potentially have to leap from platform to platform in a nifty manner. Some development tools are better at that than others. There will likely be an increased premium on using platform agnostic tools.

Cross-platform tools, like perennial favourite JavaScript, and newer tools like Xamarin, which helps Microsoft’s Windows-centric C# to play nicely in other environments, are looking like good bets.

It’s not the case that platform-specific tools are always a poor choice – many are excellent. It’s just that being nimble is likely to have an increased premium going forward.

Client-Server Relationships

Resetting and repurposing interactive exhibits is generally a hefty downtime operation. In a rapidly changing landscape it might be beneficial to ensure that there are central control servers to enable engineers to enact local and museum-wide changes in a quicker and more organised fashion.

Wiring-in exhibits as client machines operated remotely will, in many cases, enable them to be more adaptable and responsive to societal change.

BYOD (Bring Your Own Device)

This is something that museums had started to get hip to even before the pandemic. The majority of visitors bring with them a powerful personal imaging device in the form of their phone (or in some cases a tablet or other device). Why not utilise the device in visitor’s own pocket with custom apps delivering guided tours, exhibit extension, and even Augmented Reality experiences?

In a hands-off age it makes even more sense. The idea of handing out dozens of touchscreen devices to be passed around visitors is rapidly losing its appeal. BYOD fits well with goals of touch confinement and increased awareness of hygiene as a front-line barrier.

As a slight mitigating sentiment, I just wonder whether museums, being one of the few environments where people can get away from the allure (tyranny?) of their phones, might be losing something inherently calming and contemplative if they lean too heavily on this facility.

Outcome Orientated

This is something that Josh Goldblum, mentioned recently over at MuseumNext. It’s all about designing projects that are centred around outcomes, both educational and experiential, rather than technology solutions.

It means that rather than saying ‘Let’s do a VR project’, we keep ourselves focussed very much on the ‘why?’ – the outcomes we want to deliver to our audiences.

Of course, every project should have this kind of thinking at its heart – but you notice its prioritisation much more in certain projects over others. Too often an exhibit appears to have been designed to showcase an emerging tech, rather than bring visitors closer to the subject matter.

Projects that have managed to keep a firm handle on their outcome goals are going to find the act of pivot from one format to another a lot easier to manage than those that were relying on the technological environment itself to provide the audience thrills!

In conclusion – I hope these ideas have provided some initial food for thought. It is of course, difficult to predict exactly what museum provision is going to look like as we emerge from this crisis, but I am pretty sure we will all have to be more flexible and adaptable in our approach to experience design.

Adaptable design also goes beyond pandemic response. It has the potential for further benefits in areas such as accessibility, custom learning, environmentalism, age-appropriate delivery, and more. I’d love to hear more of your ideas around this area in the comment section below.